This was a talk presented as part of the Centre for Creative and Cultural Research’s seminar series back in 2017. I was going to turn in into an article, but that’ll probably never happen, so here it is as a blog post!

Let’s play a game.

Headline Roulette is a very simple game. Presented with the title of a digitised newspaper article drawn at random from Trove’s collection of more than 200 million you are challenged to guess the year in which the article was published. Sounds easy, but you only get ten guesses. It’s sort of like a cross between hangman and The Price is Right.

Despite its simplicity, I’ve known it to unleash the competitive instincts of a workshop full of historians. But for me, Headline Roulette is important because it provides an example of what becomes possible once we make cultural heritage collections available online. Our interactions are no longer limited to conventional modes of viewing or reading – we can play.

Of course there are many ways we can play with the past. Strategy or simulation games allow us to play out historical situations. Such games are themselves now a subject for academic study, not only for their teaching value, but as platforms for mounting scholarly arguments. Game technologies are commonly used in the creation of historical reconstructions or virtual worlds.

An increasing number of cultural institutions are inviting the public to play with their collections – to remix images, or build 3D models. Entries in the annual GifItUp competition use openly licensed or copyright-free images from collections around the world to create animated gifs. Interfaces are moving beyond the obligatory search box to provide opportunities for rich, exploratory browsing.

I’m interested in play as research practice, as a way of engaging with, and understanding, cultural heritage collections. I play with collections to expose perspectives, uses, meanings, and implications. I build engines for the multiplication of contexts.

Making a move

The Vintage Face Depot is a Twitter bot – a simple program that interacts with people through social media. Tweet a photo of yourself to @facedepot and the bot will respond with a new, improved version of you. Your face will be replaced by a vintage visage extracted from Trove’s digitised newspapers.

The face transplant process makes no attempt to be seamless. The new face is simply pasted atop the old. However, a degree of transparency does allow some of your features to show through – sometimes it’s not clear how much of the resulting image is really you.

And that’s the point.

The Vintage Face Depot builds on a series of experiments applying facial detection algorithms to cultural heritage collections.

Like Eyes on the past, the Vintage Face Depot explores the boundaries between art, play, and downright creepiness to ask questions about the ways we connect to the past; to explore the fragility of history, and the limits of empathy. How much of the result is really us.

Part of the Vintage Face Depot’s fun is the possibility that the choice of face might not be completely random. Some customers assume the bot is much smarter than it is, and look for some link between faces. But the only link is a url to the original article in Trove – a debt of recognition passed on to the observer for payment.

Computer algorithms are simply sets of instructions. In the case of facial detection, images are examined through a moving window and given a score against a series of pre-determined patterns. But enacted in a public space, in response to a user-contributed photograph, these algorithmic processes produce something that is open to reflection, exploration, and feeling.

Bethany Nowviskie describes the possibilities of a ‘ludic algorithm’:

a constrained, generative design situation, opening itself up — through performance by a subjective, interpretive agent — to participation, dialogue, inquiry, and play within its prescribed and proscriptive “computational spaces”.

Instead of simply generating results, ludic algorithms can serve as ‘open, participatory, exploratory devices’ – as sources of provocation and inspiration.

The value of computation to the humanities need not be measured in functional efficiencies or quantitative power. As Nowviskie, Ramsay, Rockwell, Sinclair, and others have argued, algorithmic processes can play around with our expectations of textual sources, opening them to new interpretative possibilities. Confronted with an ever growing abundance of digital texts, Ramsay extols the benefits of ‘screwing around’ as a research methodology. Sinclair and Rockwell have developed Voyant Tools, a sophisticated, web-based, text analysis platform that provides users with ‘toys’ that can be easily embedded within their own analyses. They explain:

We call it a toy not to demean it, but because rhetorically it invites playing around with the text by means other than reading. A toy is a particular interpretation in place – a hermeneutical thing that is an integral part of the essay.

Ludic algorithms and hermeneutical toys draw on other experiments in textual play. In the literary world the Oulipo movement sought to tinker with the constraints of composition. Lisa Samuels and Jerome McGann suggested that the deliberate misreading of a text, what they termed ‘deformance’, could yield critical insights. More recently, Mark Sample has argued for a ‘deformed humanities’ where we learn about things by breaking them.

And yet, the idea of ‘deforming’ the historical record seems to be fraught with professional and epistemological dangers. We generally seek to avoid charges of ‘fabrication’ or ‘invention’. Except when we don’t.

The historical record is already broken, biased, fragile, and fragmentary. We use our imaginations to fill the gaps. Whether expressed as a hypothesis or as a work of historical fiction, we play around with the possibilities of the past to construct a workable narrative. The difference between historical ‘fact’ and historical ‘fiction’ is not necessarily the role of invention, but in the rules of the game.

Counterfactuals offer a more deliberate and structured form of history play. A counterfactual is a creative reimagining of a past that never was, aimed at revealing perspectives and possibilities too quickly closed and forgotten. As Sean Scalmer notes, counterfactuals can be used to test theories or explore limits; they can ‘suggest new sources of data’. They are also fun:

‘Conventions can be disregarded, or even mocked. Worlds might be remade, the tyrannical overthrown, and the humble elevated. New orders can be imagined.’

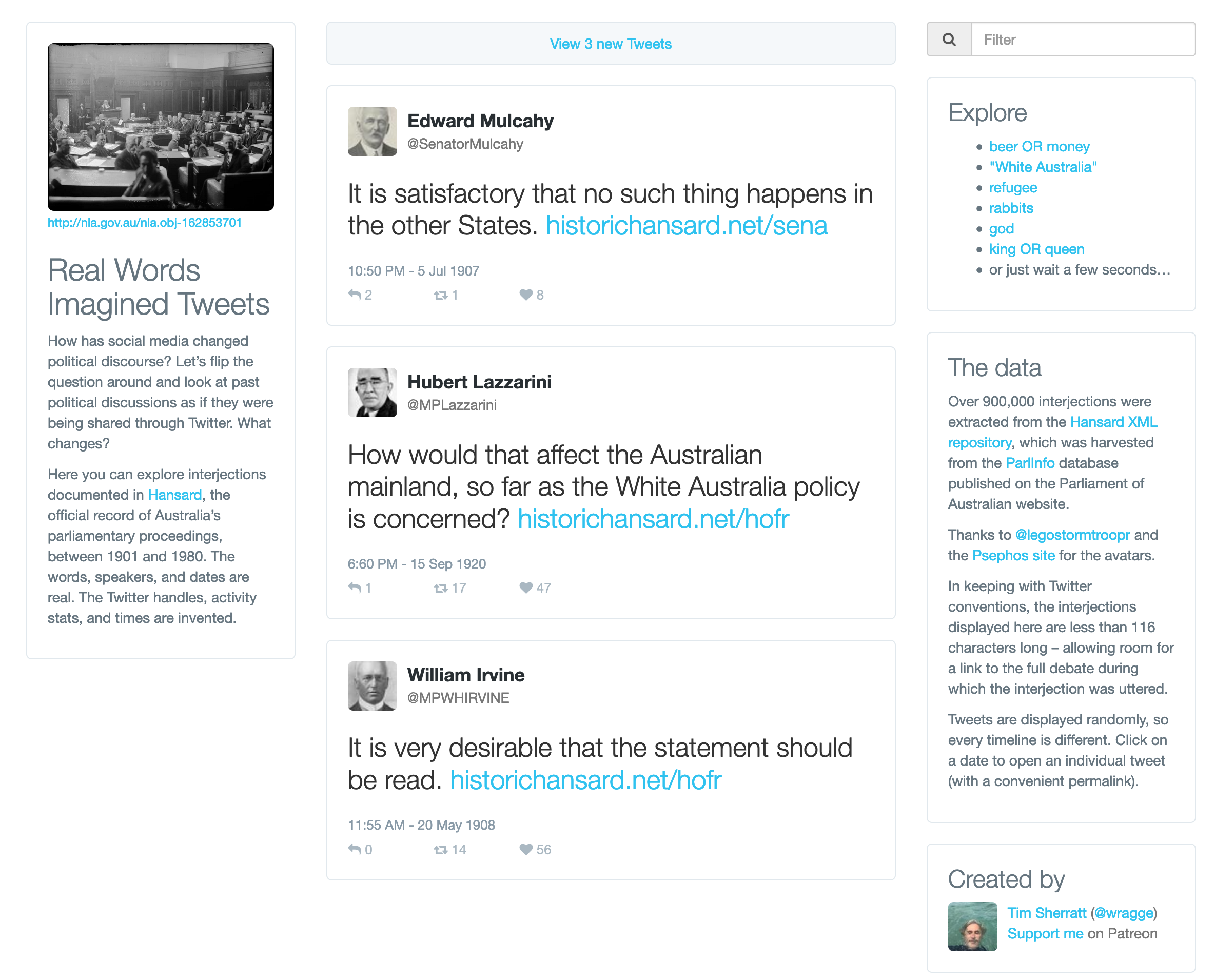

Recently I extracted nearly a million interjections from Hansard, the record of Australia’s parliamentary proceedings from 1901 to 1980. As I fiddled with different presentation methods, I started to see the interjections, often hurled across the chamber in anger or in jest, as something akin to tweets – quick, pithy, and pointed. What would happen, I wondered, if we reimagined interjections from a century ago in an age of social media.

Real Words :: Imagined Tweets is, as the name suggests, a blend of fact and fiction. Real words from real people presented as fake tweets, complete with algorithmically generated activity stats. Tweets are presented in random order, building imaginary conversations across the decades. We’re left to ponder the style of political discourse, both past and present; to make guesses about context and meaning.

As with counterfactuals, it is the interplay between source and speculation that creates space for interpretation and discovery. These inventions have meaning because they are anchored to something that can be independently known. Like the results of the Vintage Face Depot, each tweet provides a link to the full record of the debate within which the interjection was uttered. This matters. There are rules to this game.

Playing by the rules

Philosophers, anthropologists, cultural theorists, and others, have devoted much time to the meaning of play. The development of game studies over recent years has encouraged further examination of questions such as the relationship of play to ordinary life, the role of rules in defining a game, and the possibility of serious play.

Ian Bogost, the media theorist and game designer, argues in his recent book that ‘the basic experience of play is not letting loose or doing whatever you want, but carefully and deliberately working with the materials one finds in a situation’. Play is, he suggests, ‘exploring the free movement present in a system of any kind, where system might refer to a social system as much as a machine assembly’. Instead of playing with things, Bogost encourages us to find the play in things.

Cultural heritage collections are complex systems constituted through processes of selection, description, preservation, digitisation, and access. Ben Ennis Butler, Sam Hinton and Mitchell Whitelaw consider whether playful interfaces can help users engage with this complexity. Like Bogost, they point to the pleasures that come from the exploration of ‘underlying patterns and structures’, and suggest that playful interfaces might support modes of discovery that are ‘more likely to be open-ended, experimental, and driven by curiosity and intrinsic enjoyment’.

Headline Roulette, the Vintage Face Depot, and even Real Words :: Imagined Tweets employ a deliberately playful approach to cultural heritage collections, but they are still discovery interfaces. They use computational processes to expose randomly-selected resources – to enlarge our expectations, to surprise us. The links they provide back to the original resources are not simply attributions. They are gateways.

I’ve created a number of Twitter bots over recent years. @TroveNewsBot and @TroveBot are perhaps the most interesting. As well as sharing random items from Trove, they respond to public queries. By tweeting a few keywords at them, you can search Trove without ever leaving Twitter. @TroveNewsBot also keeps up an automated conversation with the ABC News and The Guardian, offering historical newspaper articles in response the the latest headlines.

In contrast to the complex behaviours of my Trove bots, the People of Australia simply shares the names of people drawn from early naturalisation records in the National Archives of Australia. I made it in an evening – a response of sorts to the election of Donald Trump.

Bots are everywhere these days. Remixing content, playing with texts and images – making art. There are many Twitter bots sharing resources from cultural heritage organisations, and I think they provide an interesting example of the ‘free movement’ we can find in collection management systems. Digital collections don’t need to be experienced through a search interface, or even a website. They can be mobilised, released into online spaces where people already congregate. The randomness of the bots’ offerings stands in contrast to institutional processes of selection and curation. As Steve Lubar notes, they draw attention ‘to the choices we take for granted’.

Collection bots are versions of ourselves, unable to contain our excitement at our latest discoveries. Look at what I found! They point to the play, to the fun, of research. But they also offer glimpses of a larger unknown.

Critically analysing the ‘black box’ metaphor that we often rely on in describing complex technological systems, Bethany Nowviskie argues that ‘nobody lives with black boxes more than the modern humanities scholar’. Beyond the proprietary systems she uses to find and manage our sources, the humanities researcher experiences black boxes because:

she operates on datasets that, generally, come to her through the multiple, muddy layers of accident, selection, possessiveness, generosity, intellectual honesty, outright deception, and hard-to-parse interoperating subjectivities that we call a library.

Or an archive, or museum… The shapes, histories, and meanings of our cultural heritage collections are ultimately unknowable. We live with this, we work with this. As Nowviskie notes:

It is the game of the scholar to reverse-engineer lost, embodied, material processes, whether those processes are the workings of ancient temple complexes or of nineteenth-century publishing houses, and to interpret and fashion narratives from incomplete information.

I’ve spent a lot of time reverse-engineering RecordSearch, the online database of the National Archives of Australia. Over the years, I’ve developed and maintained a series of tools, screen-scrapers, and harvesters to extract useful data from the web interface. I wouldn’t say it was fun – it’s often painful and frustrating work – but solving its many puzzles does offer a certain pleasure.

Terms like ‘data mining’ and ‘text mining’ fly around all the time, making it seem as if the the accumulation of data is a mechanical process – as if we’re just digging it up. But the practice of screen scraping, or of liberating data from any cultural heritage source, is not simply extractive – it’s iterative and interpretative. It’s a process through which you begin to understand how the data is organised, what its limits and assumptions are, what its history is. What it means. We’re not just taking things out, we’re putting them back.

Frederick Gibbs and Trevor Owens argue that historical data need not be deployed solely as statistical evidence. ‘It can also help’, they suggest, ‘with discovering and framing research questions’ – questions, not answers; interpretation not calculation. Gibbs and Owens describe an ‘iterative interaction with data as part of the hermeneutic process’.

It doesn’t seem unreasonable to characterise this process as ‘play’. It is, as Bogost suggests, an exploration of the ‘free movement’ in a system. I don’t play with RecordSearch, but I do try to find the play in RecordSearch – the opportunities to capture, move, transform, and build with its data. This play is not subject to an explicit set of rules, but rules do emerge as play proceeds – we start to understand what works and what doesn’t, and where the boundaries are.

But these rules themselves are open to analysis, critique, and play. In their discussion of the use of games in history teaching, Kevin Kee and Shawn Graham describe the possibilities of ‘meta-gaming’ – of not simply playing, but modifying, games. Meta-gaming can ‘exploit bugs or features of a game in a way that was not originally intended by the game designers’. We can change the rules.

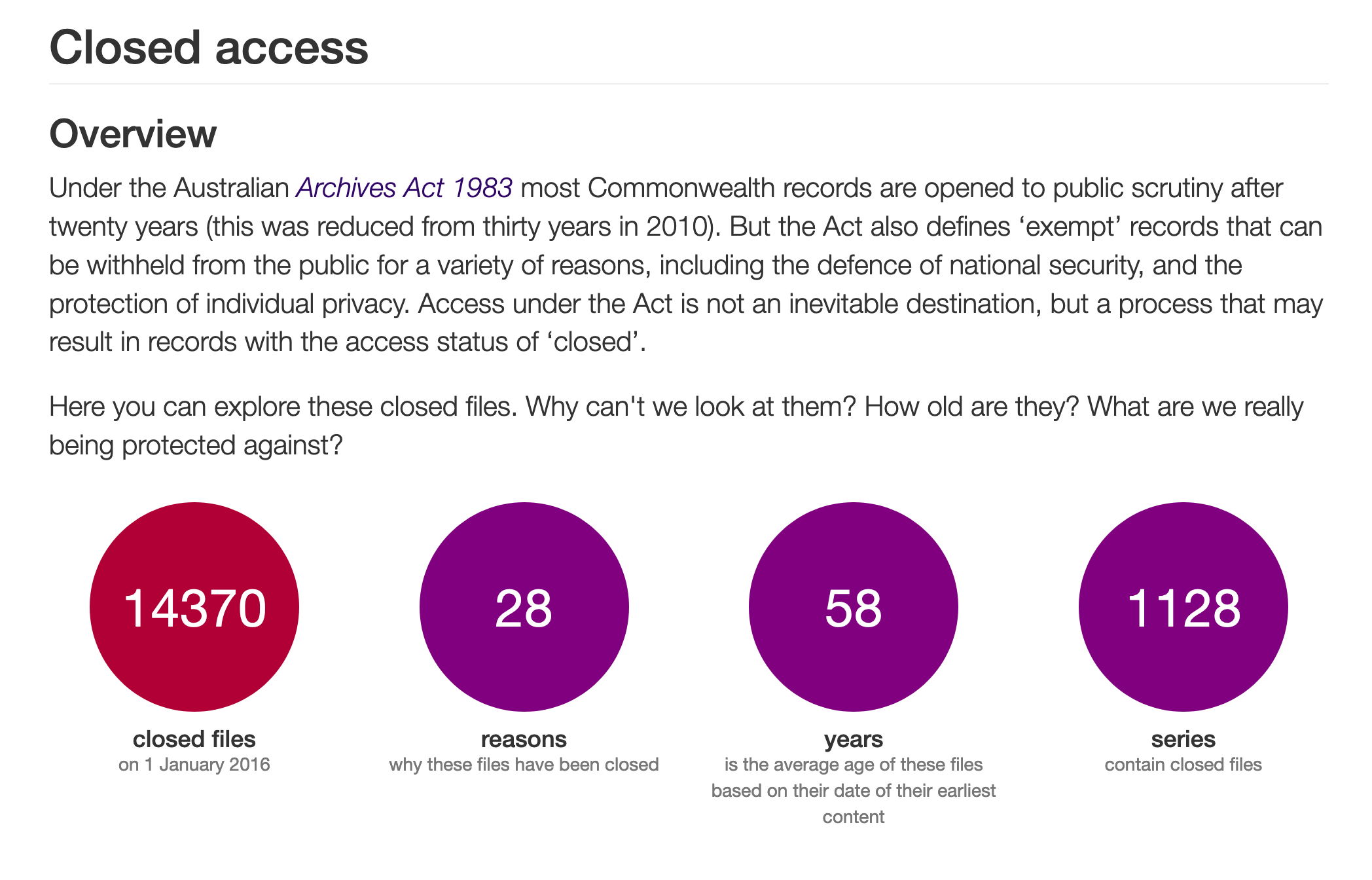

Under the Archives Act, government records more than twenty years old are expected to be opened to the public. However, the act also defines a number of exceptions to this rule – for example, records that endanger national security or infringe an individual’s privacy can be completely, or partially, withheld from scrutiny. The process of assessing records against this set of exemptions is called ‘access examination’.

The vast majority of records are opened without problem – they are, after all, more than 20 years old. But a significant number are not. While you can’t actually see or use these records, RecordSearch does provide some information about them. So in January last year I decided to see what we couldn’t see. I harvested the details of all 14,370 files that had been through the process of access examination and withheld from public view. In RecordSearch these files have the access status of ‘closed’.

I used this data to create Closed Access, a site that lets you explore the files from a variety of angles – such as the reasons why they were closed, when decisions were made about them, how old they are, and which government agencies created them. Although all this information is contained within RecordSearch, your ability to use it is limited – for example, you can’t filter your search results by the reason a file was withheld.

The rules have now changed. By removing this data from RecordSearch I’ve been able to flip it around, and make inaccessible files the focus of discovery – perhaps creating in the process the most frustrating search interface ever devised. This is both playful and pointed.

The aim of the game

In his book, Exploratory Programming for the Arts and Humanities, Nick Montfort offers a number of answers to the question ‘Why program?’. Programming improves our thinking, it can help us build a better world, and programming is fun. ‘It is enjoyable to write computer programs and to use them to create and discover,’ he argues, ‘this is the pleasure of adding something to the world, of fashioning something from abstract ideas and material code that runs on particular hardware’.

For me, much of the fun in playing with cultural heritage data comes not through solving puzzles, or finding a way through, but in ‘adding something to the world’ – in making a difference.

The aim of Closed Access is to better understand access examination as a historical process. It’s a work that enables us to ask different types of questions, but it also makes a change in the process itself. My interface is public, offering a critical commentary on the ‘official’ system. As a result of my research, the Archives has made changes to the way it describes closed files. It’s both research and intervention, history and hack.

‘Hack’ has a number of definitions, both positive and negative. Mark Olson describes the ‘hacker ethos’ as:

‘a way of feeling your way forward through trial and error, up to and perhaps beyond the limits of your expertise, in order to make something, perhaps even something new. It is provisional, sometimes ludic, and involves a willingness to transgress boundaries, to practice where you don’t belong… Whether eloquent or a kludge, a hack gets things done.’

Many of my experiments, like Eyes on the Past, or Real Words :: Imagined Tweets, were built in a couple of days. No research grants were harmed in their creation, no committees were needlessly formed. This is not because I’m a whizz-bang coder – I’m certainly not. It has to do with the nature of this work – it’s rapid, experimental, and sometimes even ephemeral. I don’t design websites, I make interventions – things that are not only of the world, but in the world. They do something.

Mostly what they do, is play around with this thing we call ‘access’. Cultural heritage organisations talk about ‘access’ all the time, particularly in relation to online collections. But what does it actually mean? I want to overturn our assumptions about access – exploring it not as a process of opening things up, but as a system of controls and limits. It’s not a state of being, it’s a struggle for meaning and power.

The way I’m approaching this struggle is through the multiplication of contexts. Context is, of course, critical to cultural heritage collections – it enables us to locate them within history and culture, to analyse their authenticity, to mobilise their value as evidence. But the descriptive systems we use to manage and explore collections represent only a privileged subset of possible contexts.

Now I’m still figuring this out, but I think what my work does is that it removes collections from these highly-controlled systems and lets them loose in a variety of new contexts. This allows unexpected features, or new uses, to emerge – we see them differently, and in that moment, the nature of access shifts, however slightly. It’s those moments I’m trying to catch and observe.

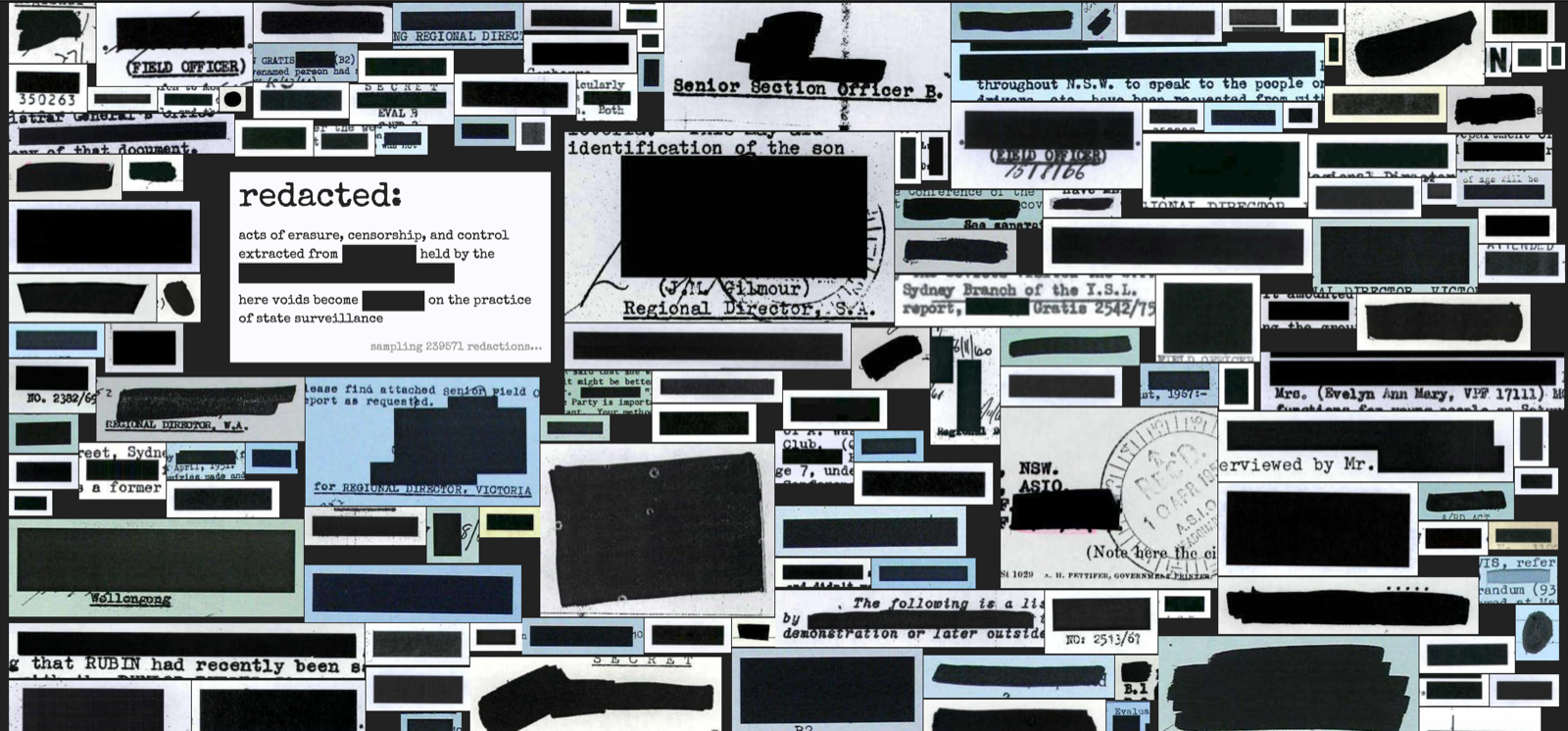

A couple of years ago I harvested all the publicly available ASIO files from the National Archives. Most of these surveillance files are ‘open with exception’. This means that sensitive parts of the files have been removed. Whole pages can be withheld, or sections of text blacked out – a process known as redaction.

A redaction is, by definition, an absence of information, and yet the frequency, density, and placement of redactions across a large collection of documents could conceivably tell us something interesting. So last year I wrote a kludgy computer vision script that found and extracted redactions from digitised ASIO files.

I’m continuing to explore the possibilities of these redactions as data points. But there was also something visually interesting about the redactions, particularly when they were assembled on masse.

Here you can browse all 250,000 redactions. But that’s not all, you can also use them as entry points to the documents they were intended to obscure.

Contexts here have been reversed, the files have been turned inside out – the limits remain, indeed the scale of redaction is emphasised, and yet within these limits, perhaps even because of these limits, we can experience the files quite differently. We are no longer simply the subjects of state surveillance, we can reverse the gaze, inspect the process, and ask new questions.

The manipulation of contexts is not mere invention. The limits of access offer both meaning and rules. We have skin in this game, its outcomes matter, what is at stake is our ability to see, and be seen, within the cultural record. Access changes who we can imagine ourselves to be.

Winners and losers

In the first half of the twentieth century, if you were deemed not to be ‘white’ and wanted to travel overseas from your home here in Australia, you had to carry special documents. Without them, you’d probably be stopped from returning – from coming home. This was ‘extreme vetting’ White Australia style.

Many thousands of these documents are now held by the National Archives of Australia. In 2011, I harvested about 12,000 images like this from RecordSearch. I then ran them through a facial detection script and created The Real Face of White Australia.

There are about 7,000 faces in this seemingly endless scrolling wall. And that’s from just a small sample of the White Australia records. It’s powerful, compelling and discomfiting. But the power comes not from any technical magic, but from the faces themselves – from what we feel when meet their gaze. Once again the records have been turned inside out – instead of seeing files, metadata, or a list of search results, we see the people inside.

Bethany Nowviskie argues that it’s not enough to unpack the ‘black boxes’ that shape our political and social lives. Simply revealing their contents does not challenge their power. Instead she suggests we play with them.

‘the most constraining algorithm in any ludic or hermeneutic system becomes just another participant in the process. It opens itself to scholarly interpretation, subjective or artistic response, and practical enhancement or countering measures. And in that way, it begins to open itself to resistance.’

The ASIO and White Australia files are both records of government surveillance aimed at monitoring potential threats – whether due to the subject’s political beliefs, or the colour of their skin. In playing with the records, we are not only creating new perspectives, new contexts, we are taking a stand against the systems that created them.

References

Ian Bogost, Play Anything: The Pleasure of Limits, the Uses of Boredom, and the Secret of Games, (New York: Basic Books, 2016).

Ben Ennis Butler, Sam Hinton, and Mitchell Whitelaw, “Playing with Complexity: An Approach to Exploratory Data Visualisation” (ACUADS Conference 2011: Creativity: Brain – Mind – Body, Canberra: Australian Council of University Art and Design Schools, 2011).

Frederick W. Gibbs and Trevor Owens, “Hermeneutics of Data and Historical Writing,” in Writing History in the Digital Age, ed. Jack Dougherty and Kristen Nawrotzki, 2011.

Kevin Kee and Shawn Graham, “Teaching History in an Age of Pervasive Computing: The Case for Games in the High School and Undergraduate Classroom,” in Pastplay: Teaching and Learning History with Technology, ed. Kevin Kee (University of Michigan Press, 2014).

Steven Lubar, “Museumbots: An Appreciation,” On Public Humanities (blog), August 22, 2014.

Nick Montfort, Exploratory Programming for the Arts and Humanities (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2016).

Bethany Nowviskie, “Ludic Algorithms,” in Pastplay: Teaching and Learning History with Technology, ed. Kevin Kee (University of Michigan Press, 2014).

Bethany Nowviskie, “A Game Nonetheless,” Bethany Nowviskie (blog), March 15, 2015.

Mark J. Olson, “Hacking the Humanities: Twenty-First-Century Literacies and the ‘Becoming Other’ of the Humanities,” in Humanities in the Twenty-First Century: Beyond Utility and Markets, ed. Eleonora Belfiore and Anna Upchurch (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 238.

Stephen Ramsay, “The Hermeneutics of Screwing Around; or What You Do with a Million Books,” in Pastplay: Teaching and Learning History with Technology, ed. Kevin Kee (University of Michigan Press, 2014).

Geoffrey Rockwell and Stéfan Sinclair, Hermeneutica: Computer-Assisted Interpretation in the Humanities (Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: The MIT Press, 2016).

Lisa Samuels and Jerome J. McGann, “Deformance and Interpretation,” New Literary History 30, no. 1 (February 1, 1999): 25–56, https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.1999.0010.

Sean Scalmer, “Introduction,” in What If? Australian History as It Might Have Been, ed. Stuart Macintyre and Sean Scalmer (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2006), 1–11.